Sources and research methodology for the study of the historical figure of Jesus of Nazareth and the documents that refer to him, evangelical and extra-evangelical.

Introduction

As anticipated in a previous article, until the 18th century there were no doubts about the existence of Jesus of Nazareth. What was narrated about him in the Gospels and in the existing extra-biblical sources was not questioned. The advent of the Enlightenment, on one hand, gave rise to doubts and disputes about the figure of the Nazarene but, on the other hand, paradoxically favored the birth and development of research that would use the historical-critical method to investigate the reliability of the sources themselves. This method, which includes a set of philological and hermeneutical principles and criteria developed beginning in the 17th century, is universally applicable – thus not only to the Gospels and what has been written in reference to the Nazarene – and aims to reconstruct a text in its original form, at the moment when different variants have been handed down, evaluating the historical content of the text’s narrative itself.

The persistent, often ideological, application of the historical-critical method has, however, led to a sort of division between the “historical Jesus” (pre-paschal) and the “Christ of faith” (post-paschal) and forced the Catholic Church itself to resort to biblical exegesis, to philological research on the Gospels, and to archaeology to dispel all doubts about the historical existence of Jesus, coming to hold, particularly in the context of the Second Vatican Council (Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum, 18-19), “that the four Gospels, whose historical character the Church unhesitatingly asserts, faithfully hand on what Jesus Christ, while living among men, really did and taught for their eternal salvation until the day He was taken up into heaven”.

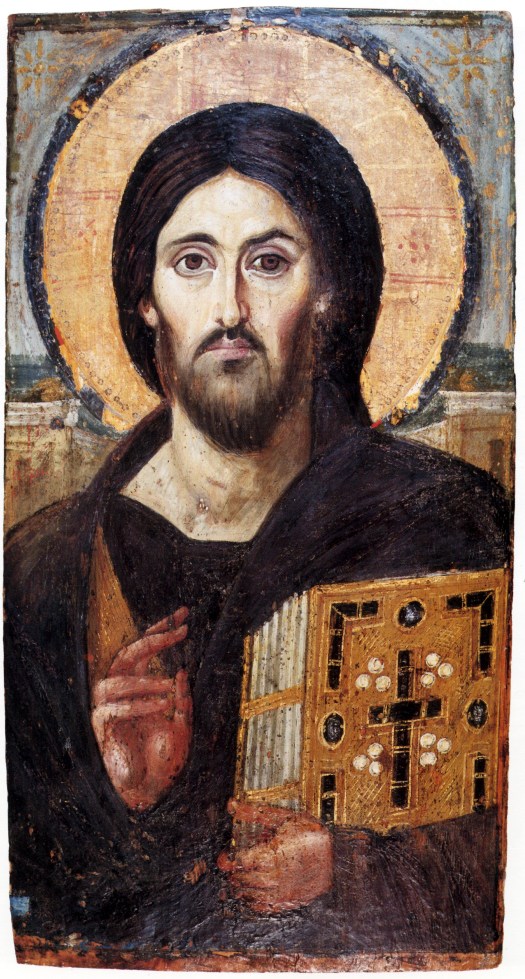

The Catholic Church’s claim, of course, is unique, as it combines in the figure of Jesus of Nazareth both the ‘historical Jesus’ and the ‘Christ of faith’. Nevertheless, to this day the vast majority of historians (whether they be Christian, Jewish, Muslim, of other religions, or non-religious) have no doubt in affirming that the man Jesus of Nazareth really existed. Not only that, but there is an ever-increasing amount of historical and archaeological evidence that not only confirms many details about his earthly existence but also legitimizes what is narrated about him by the documents that most refer to him: the Gospels and other New Testament writings.

The approach to the “historical Jesus”

Historical research on Jesus of Nazareth is generally divided into three phases: 1

- The First Quest (or Old Quest ), inaugurated by Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768) and whose main exponent was the French scholar Ernest Renan (famous for his Life of Jesus).

- The Second Quest (or New Quest), effectively pioneered by the famous Albert Schweitzer (1875-1975), the first to highlight the limits of the First Quest, but officially launched in 1953 by the German Lutheran theologian Ernst Käsemann (1906–1998), a student of Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976), in response to the latter, who, as a leading exponent of a period known as No Quest , argued that there was no need, for a Christian, to resort to historical investigation on Jesus of Nazareth, as faith alone should be sufficient to believe.

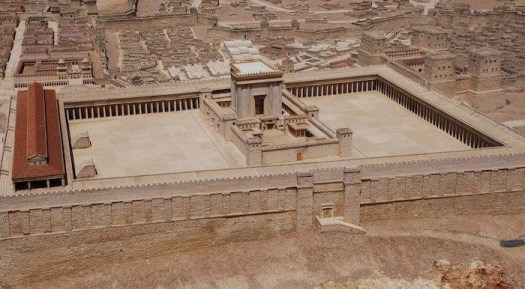

- The Third Quest, the prevailing one today. It includes scholars like David Flusser (1917-2000), author of fundamental writings on ancient Judaism and convinced, like many other contemporary Israeli Jews, that the Gospels and Pauline writings represent, along with the Qumran Scrolls, the richest and most reliable source for the study of Second Temple Judaism, as other materials have been completely lost with the great catastrophes of the three Jewish Wars (between 70 and 132 AD).

The so-called First Quest, in summary, is distinguished by the systematic and ideological denial, according to the criteria of rationalist Enlightenment rationalism, of all miraculous and prodigious events related to the figure of Jesus, without questioning his existence as a man and historical figure, but soon encountering the limits derived from its own ideology, as highlighted by Albert Schweitzer. None of the protagonists of this research phase, however, ever focused on the historical context and archaeological sources, although Renan romantically referred to Palestine as a “fifth gospel”.

The Second Quest, for its part, is characterized by recognizing the need not to outright reject the “Christ of faith” tout court, as happened in the previous phase, but to take into consideration all the material that has come down to us about Jesus of Nazareth, including the miraculous events, in a critical and not aprioristic way.

The same applies, even more so, for the Third Quest, whose proponents focus more on the historical, religious, and cultural context of Judea at the time, which in recent decades has become better known to us thanks to the discovery of the Qumran manuscripts (1947) and to sensational archaeological discoveries.

The sources

We can group the sources that provide us with information about Jesus of Nazareth into three types, which we will analyze:

- Non-Gospel sources: on one hand, the non-Christian sources; on the other, the Christian sources (which are further divided into: apocryphal, i.e., the apocryphal Gospels, the agrapha and the logia; canonical, namely the Pauline Letters, the Acts of the Apostles, and other canonical documents);

- Gospel sources : the four canonical Gospels;

- Archaeological sources;

Non-Gospel sources: non-Christian historical documents

Among these sources, there are references to Jesus or, especially, to his followers. They are the work of ancient non-Christian authors such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Pliny the Younger, Lucian of Samosata, Marcus Aurelius, and Minucius Felix. References to Jesus of Nazareth can also be found in the Babylonian Talmud. The information provided by such sources does not prove to be particularly useful, as they do not give detailed information about Jesus. Sometimes, indeed, wanting to diminish the importance or the legitimacy of the cult that originated from him, they refer to him in an imprecise and slanderous manner, speaking of him, for example, as the son of a hairdresser, or of a magician, or again of a certain Panthera, a transliteration, and consequently a misinterpretation, of the Greek term parthenos (virgin), already used by the early Christians in reference to the person of Christ, son of the Virgin.

Non-Christian historical documents, however, already allow for some confirmation of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth, albeit through fragmentary information. 2 The oldest and most detailed among them is the famous Testimonium Flavianum, 3 by the the 1st century A.D. Jewish historian Josephus Flavius.

The passage in question is found within the work Jewish Antiquities (XVIII, 63-64). Until 1971, a version circulated that referred to Jesus of Nazareth in terms considered excessively sensationalist and devout for an observant Jew such as Josephus Flavius. It was suspected, in fact (although several historians do not share this opinion), that the Greek translation known until then had been subject to interpolation by Christians. In 1971, however, Professor Shlomo Pinés (1908-1990), from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, published a different translation, in line with what he found in a 10th-century Arabic manuscript, the Universal History, by Agapius of Hierapolis (died in 941). This text is considered more reliable than the Greek one transmitted until that time, since it does not show possible interpolations, so much so that it is universally considered, to date, the oldest testimony on Jesus of Nazareth within a non-Christian source.

We report the passage below:

At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. His conduct was good, and [he] was known to be virtuous. And many people from among the Jews and the other nations became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die. But those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship. They reported that he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion, and that he was alive; accordingly he was perhaps the Messiah, concerning whom the prophets have recounted wonders.

Another important testimony is that of the pagan Tacitus, who, in his Annals (ca. 117 AD), writing about Nero and the fire of Rome in 64 A.D., reports that the emperor, to divert the rumors that wanted him guilty of the disaster that had almost completely destroyed the capital of the Empire, had blamed the Christians, known then by the people as Chrestiani :

Christus [Chrestus], from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular (Annals, XV, 44).

Non-Gospel sources: apocryphal Christian documents

Agrapha and Logia

The Agrapha, meaning “unwritten”, are brief sayings or aphorisms attributed to Jesus and that, however, have been transmitted outside of the Holy Scripture (Graphé ) in general or the Gospels in particular.

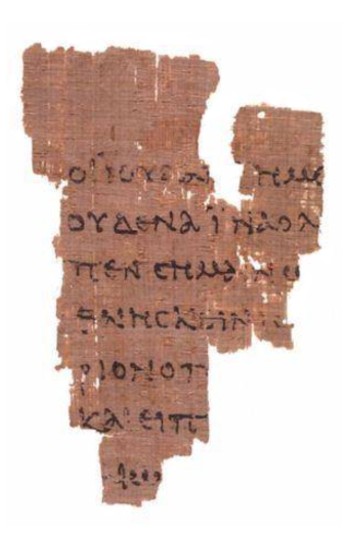

A similar discussion can be made for the Logia (sayings), which are also short sentences attributed to the Nazarene, very much like the Agrapha, except for the fact that the latter are more typically found in works of the Church Fathers4 or in certain particular codices of the New Testament, while the Lògia are predominantly contained in fragments of ancient papyri discovered more recently especially in Egypt.5

Such sources are not considered authoritative, from a historical point of view, as, at least for the most part of them, their historical reliability is not certain.

Apocryphal Gospels

The Apocryphal Gospels (a term that derives from Greek and means something to hide or that is reserved for a few and, by extension, a work whose author is uncertain) are those numerous (to date about fifteen) heterogeneous documents about Jesus of Nazareth not accepted into the Christian biblical canon for various reasons: the lateness of these compared to that of the canonical Gospels (on average a century difference, where for the canonical Gospels we speak of a composition dating back to the second half of the 1st century A.D.); the textual form distinct from the canonical one (the latter characterized by expressive and linguistic coherence and simple style, free of sensationalism, in contrast with the legendary and fairy-tale aura of the apocrypha); the intention to transmit doctrines in contrast with the official ones (these are often Gnostic documents, crafted “artfully” in order to spread new doctrines and justify political and religious positions of individuals or groups).

It should be noted that the reliability of such documents has not been completely excluded and discarded (for example, in the Proto-Gospel of James, there are stories and traditions about the childhood of Jesus, the life of Mary, or specific apostles that have entered into the Christian popular imagination) and that these are able to provide a religious and cultural overview of the environment of the 2nd century A.D. However, the contradictions contained within them, the non-conformity with texts considered official, as well as the obvious deficiencies in terms of doctrine, truthfulness, and independence of judgment do not allow them to be attributed authority from a historical point of view, as is also the case for the Agrapha and the Logia.

Non-Gospel sources: canonycal Christian documents

Pauline letters and Acts of the Apostles

The Pauline letters, or Letters of Saint Paul the Apostle, are part of the New Testament. They were written between 51 and 66 A.D. by Paul of Tarsus, better known as Saint Paul, defined as the Apostle of the Gentiles because with him Christian preaching crossed the borders of Western Asia. He never met Jesus personally, yet his writings represent the oldest documents on the Nazarene, in addition to establishing beyond a shadow of a doubt that the kerygma, the announcement about Jesus’ identity as the son of God born, died, and risen according to the Scriptures, was already fixed less than twenty years after his death on the cross.

Further information can be found in other writings of the New Testament, especially in the Acts of the Apostles. These are a chronicle of the deeds of the apostles of Jesus of Nazareth following his death, with particular attention to Peter and Paul of Tarsus. The authorship of this work is attributed to the author of one of the Synoptic Gospels, Luke (or Lucan), and, most likely, they were written between 55 and 61 A.D. (the narrative abruptly stops with the first part of Paul’s life and imprisonment in Rome, not with his death, which occurred a few years later).

If one analyzes the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline Letters, it is possible to extrapolate a biography of Jesus of Nazareth outside of the Gospels and notice how, although sparse in details, this is entirely consistent with what is narrated by the Gospels themselves.

Indeed, we can deduce from the writings in question that Jesus: was not an angelic entity, but “a man” (Romans 5:15); “born of a woman” (Galatians 4:4); a descendant of Abraham (Galatians 3:16) through the tribe of Judah (Hebrews 7:14) and the house of David (Romans 1:3); his mother was named Mary (Acts 1:14); he was called the Nazarene (Acts 2:22 and 10: 38) and had “brothers 6” (1 Corinthians 9:5; Acts 1:14), one of whom was named James (Galatians 1:19); he was poor (2 Corinthians 8:9), gentle and meek (2 Corinthians 10:1); received baptism from John the Baptist (Acts 1:22); gathered disciples with whom he lived in constant and close relationship (Acts 1, 21-22); twelve of them were called “apostles”, and this group included, among others Cephas, that is, Peter, and John (1 Corinthians 9:5; 15, 5:7; Acts 1:13. 26); during his life, he performed many miracles (Acts 2:22) and went about doing good and healing many people (Acts 10:38); once appeared to his disciples gloriously transfigured (2 Peter 1:16-18); was betrayed by Judas (Acts 1:16-19); on the night of betrayal, he instituted the Eucharist (1 Corinthians 11:23-25), agonized in prayer (Hebrews 5:7), was insulted (Romans 15:3) and preferred over a murderer (Acts 3:14); suffered under Herod and Pontius Pilate (1 Timothy 6:13; Acts 3:13; 4:27; 13:28); was crucified (Galatians 3:1; 1 Corinthians 1:13. 23; 2:2; Acts 2:36; 4:10) outside the city gate (Hebrews 13:12); was buried (1 Corinthians, 15:4; Acts 2:29; 13:29); rose from the dead on the third day (1 Corinthians 15: 4; Acts 10:40); then appeared to many (1 Corinthians, 15:5-8; Acts 1:3; 10:41; 13:31) and ascended into heaven (Romans 8:34; Acts 1:2. 9-10; 2:33-34).

From the comparison between this limited extra-biblical biography of Jesus and the more extensive one offered by the Gospels, we can deduce that in early Christianity there was consistent information circulating about the figure of the Nazarene, especially when we consider that the documents in question, although all included in the New Testament, were written by authors who were distant and independent from each other in time and space.

The Gospels

The canonical Gospels (i.e., those that are part of the official biblical canon of Christian Churches and which even non-Christian scholars today recognize as having historical authority and authenticity) are four: “according to” Matthew, Mark, Luke (these first three Gospels are also called synoptic7) and John.

The term “gospel” is the English translation of the Greek εὐαγγέλιον (euangèlion), latinized into evangelium and having several meanings.

On one hand, in classical Greek literature, it signifies everything related to good news, namely: the good news itself; a gift given to the messenger who brings it; the votive sacrifice to the deity as thanks for the good news.

In a Christian sense, however, it refers to the good news tout court and is always related to Jesus of Nazareth. It can be, in fact:

- the Gospel about Jesus , that is the good news passed down by the apostles about the work and teaching of the Nazarene, but above all his resurrection and eternal life (and, in this sense, it also extends to the documents known to us today as the Gospels);

- the Gospel of Jesus, that is the good news brought, this time, by Jesus himself, which is the Kingdom of God and the fulfillment of the messianic expectation;

- Jesus-Gospel, in this case the person of Jesus, given by God to humanity.

Formation of the Gospels

In the early years after the death of the Nazarene, the “gospel” (this word now encompassed all three meanings just listed) was transmitted in the form of catechesis, a term that derives from the Greek κατήχησις, katechèsis.8 Jesus himself had left nothing written, like the other great Jewish masters of his time, called “mishnaic” (from about 10 to 220 A.D.), known as Tannaim,9 who orally transmitted the written Law and the tradition that was forming, from teacher to student, through constant repetition of Scripture passages, parables, phrases, and sentences (midrashim, plural of midrash) constructed in a poetic manner and sometimes in the form of chant (we have an example of this in the Koran), often using rhetorical figures such as alliteration, to facilitate the mnemonic assimilation of what was proclaimed.

However, the wide ecumenical ‘resonance’ generated precisely by this ‘good news’ prompted the nascent Church to want to put in writing, and then translate it into the cultured and universal language of the time (Greek) the proclamation of the life and works of Jesus of Nazareth. Indeed, we know that, already in the ’50s of the 1st century, numerous writings containing the ‘gospel’ (Luke 1, 1-4) were circulating. The development of a written New Testament,10 however, did not exclude the continuation of oral catechetical activity. It can be said, indeed, that the announcement continued, with both means, in tandem.11

In the 1950s, we also know from the tireless Paul (who communicates this to the Corinthians in his second Letter to this community) of a brother (and not just any brother, but “the” brother) praised in all the Churches because of the Gospel he had written. It is undeniable that he was talking about Luke, being the brother who had been closest to him on his journeys, so much so that he narrated his exploits in the Acts.

This would confirm what has emerged from the most recent studies on the Gospels, conducted by biblical scholars such as Jean Carmignac12 (1914-1986) and John Wenham (1913-1996), namely the need to date back the four texts considered sacred by Christians by a few decades compared to what was believed until the last century.

Although nothing definitive can be stated regarding the exact date of composition of the four Gospels, according to most experts, these writings would date back to the second half of the 1st century, i.e., when many of the eyewitnesses to the events narrated were still alive. They would, however, draw on even older sources, such as the so-called Q source (from German quelle, “source”), from which Luke and Matthew would have drawn much information and which several scholars identify with an earlier version of Mark, and the logia kyriaká (sayings of/about the Lord).

Below is a schema that reports, in a non-exhaustive way, the state of research around the canonical Gospels:

- Mark. It is almost certainly the oldest Gospel (whose composition is placed between 45 and 65 A.D.) and would be at the base of the triple synoptic tradition. According to scholars, it would derive from the preaching of Peter himself, in Palestine but especially in Rome. Jean Carmignac believes that this Gospel was written, or dictated, by Peter in person, in Hebrew (or in Aramaic) around 42 and that it was then translated into Greek (as written by Papias of Hierapolis13 in his work Exegesis of the Logia Kyriaka) by Mark, hermeneutés (interpreter) of Peter, around 45 (as also supported by J. W. Wenham) or, at the latest, by 55.

- Matthew . The drafting of this Gospel is placed around 70 or 80 AD. It would be the result of a collection of speeches in Hebrew (lògia), put together and used by the apostle Matthew between 33 and 42 AD during his evangelizing activity among the Jews of Palestine (the source Q also used by Luke) and completed, according to Carmignac, not around 70, but around 5014.

- Luke . This Gospel too, according to many scholars, would have been written around 70 or 80. It is a widespread opinion that Luke’s would be the Gospel compiled in a more accurate manner, from a historical point of view, and would draw from the source Q (also used by Matthew and which would consist, in the opinion of various historians and biblical scholars, in the oldest version of the Gospel of Mark), integrated by personal research conducted in the field (as stated by the same author in the Prologue). Carmignac believes that Luke’s edition dates back to 58-60, if not even shortly after 50 (a hypothesis supported by Wenham and others).

- John. The only non-synoptic Gospel, it has long been considered the least “historical” among the Gospels, until a thorough study revealed that it is, from a geographical and chronological point of view, an even more precise document compared to the previous Gospels. The rich and precise terminology, as well as clear and unequivocal topographical, chronological, and historical information, have allowed, among other things, to reconstruct in detail the number of years of Jesus’s preaching, to date the events of Easter more accurately, according to a more precise calendar, to discover archaeological finds then identified with places he himself described in his Gospel (Pilate’s Praetorium, the Pool of Bethesda, etc.). For many, it dates back to 90-100 AD. Carmignac, Wenham and others place it, instead, shortly after 60.

The Canon

Already in the 2nd century A.D., especially in response to Marcion, who aimed to exclude the Old Testament and all those parts of the new that were not in line with his teachings (he believed, in fact, that the God of the Christians should not be identified with that of the Jews), Justin (140) and Irenaeus of Lyons (180), followed then by Origen, wanted to reaffirm that the canonical Gospels, universally accepted by all Churches, should be four. This was confirmed within the Muratorian Canon (an ancient list of the New Testament books, dating back to around 170).

To establish the “canonicity” of the four Gospels, very specific criteria were followed:

- Antiquity of the sources.15 As we have seen, the four canonical Gospels, dating back to the 1st century AD, are among the oldest and best attested sources in terms of the number of manuscripts or codices (about 24,000, in Greek, Latin, Armenian, Coptic, Old Slavonic, etc.), more than any other historical document.

- Apostolicity.16 The writings, to be considered “canonical”, had to trace back to the Apostles or their direct disciples, as with the four canonical Gospels, whose linguistic structure reveals evident Semitic traces (or “semitisms”: we will talk about this later). It should be noted that the term “according to”, placed before the name of the evangelist (according to Matthew, Mark, etc.) indicates that the four Gospels make a single discourse on Jesus in four complementary forms, which trace back to the preaching of the individual apostles from whom, in fact, the particular writings derive: Peter for the Gospel according to Mark; Matthew (and probably Mark) for that according to Matthew; Paul (and, as we have seen, also Mark and Matthew) for that according to Luke; John for the Gospel that bears his name. In practice, it is not so much the individual evangelist who writes the individual Gospel, but the community, or the Church, born from the preaching of an apostle of the Nazarene.

- The catholicity or universality of the use of the Gospels: they had to be accepted by all the main Churches (“catholic” means “universal”), therefore by the church of Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Corinth, Jerusalem, and by the other communities of the first centuries.

- Orthodoxy or right belief.

- The multiplicity of sources, that is the numerous and proven testimonies in favor of the canonical Gospels themselves (and here we return to mention, for example, Papias of Hierapolis, Eusebius of Caesarea, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Pantaenus, Origen, Tertullian, etc.).

- The explanatory plausibility, that is the comprehensibility of the text according to a coherence of cause and effect.

Historicity of Christ and the Gospels: Study Criteria

In addition to the earliest testimonies of the Church Fathers and the criteria already used in the 2nd century A.D. in documents such as the Muratorian Canon, especially in modern and contemporary times, further methods have been developed that allow us to confirm the historical data we already possess regarding the figure of Jesus of Nazareth and the Gospels.

Literary and Editorial Criteria

- Study of literary forms (Formgeschichte). This method is based on the literary analysis of the Gospels, through the classification of the Gospel passages according to different literary forms, to determine what is defined as “Sitz im leben”, that is, the life situation of the community in which the literary form arose, and thus “embody”, the existence of the Nazarene and his teachings in a living context with specific needs.

- Study of oral traditions (Traditiongeschichte). Through the study of pre-existing literary forms to the Gospels, it is possible to determine the existence of older oral traditions, even in the terminology used by the editors of the documents in question. It is possible, therefore, to identify an oral tradition of Peter (in Mark and Luke), a tradition of Paul (in Luke), a tradition of Matthew, and a tradition of John.

- Study of the editorial criteria of the evangelists (Redaktiongeschichte). This study, by comparing the content of the different oral traditions with the written literary forms, especially starting from the discrepancies between them, allows to determine that each evangelist did not just collect data to then write it down, but organized it according to his own criteria and particular needs (for example, preaching to one community rather than another), in light of which he unified all the material.

Semitisms and philological analysis

In the very first centuries of the Christian era, it was well known, as we have seen from some cited testimonies, that at least two of the canonical Gospels were originally written in a Semitic language (Hebrew or Aramaic). Over time, however, at least until Erasmus of Rotterdam (1518), the memory of such an older layer underlying the Greek language, in which the texts had come down to us, was lost. It is precisely the beginning of a serious philological study on the Gospel texts that has allowed, in modern times, to reconstruct with greater precision that typically Semitic structure that is at the base of the Gospels as we know them today.

The traces of such structure are defined as “semitisms”, and can be of various nature, according to what has been elaborated by Jean Carmignac: of loan; of imitation; of thought; of vocabulary; of syntax; of style; of composition; of transmission; of translation; multiple.

Carmignac himself believes, also in light of the study of the mishnaic tradition, that is, the oral and poetic transmission of the teaching of Jewish masters of the intertestamental17 period, that the semitisms contained in the Synoptic Gospels are so numerous and of different kinds as to make evident the fact that the Gospels, at least Mark and Matthew, were first written in Hebrew and then retranslated into Greek. By retranslating the New Testament Greek back into Hebrew, in fact, one finds in this language (more so than in Aramaic) assonances, rhymes, alliterations, and poetic riches that are not visible in Greek prose. The reason for the insistence on this aspect, by biblical scholars and scholars such as Carmignac, Wenham and many others (including various Israeli Jews18) is twofold. Establishing that a part of the Gospels was written in a Semitic language, in fact, allows, on one hand, an earlier dating by a couple of decades than what had always been assumed, thus a closer proximity both to the narrated events and to the direct (and living, at the time of writing) witnesses, who could corroborate or deny what was reported in the works on the life of the Nazarene; on the other hand, a more harmonious placement of the figure of Jesus within the social, religious, and cultural context of the time (something that the Qumran Scrolls have also contributed to).

Due to space and opportunity constraints, we cannot elaborate further on this aspect. However, it is enough to think that anyone with even a minimal knowledge of Hebrew can identify in the Gospel texts the exact structure, constructs, and lexicon of this ancient Semitic language. Upon careful reading, in fact, it almost seems that the language of the New Testament (at least that of the four canonical Gospels) faithfully mirrors, in syntactic structure, terminology, thought, and rhythm that of the Old. Here we provide only a couple among the numerous examples that could be cited.

English:

I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham

Greek:

λέγω γὰρ ὑμῖν ὅτι δύναται ὁ θεὸς ἐκ τῶν λίθων τούτων ἐγεῖραι τέκνα τῷ Ἀβραάμ

Lego gar hymìn oti dynatai o Theos ek ton lithon touton egeirai tekna to Abraam

Hebrew (one of the possible translations):

אלוהים יכול לעשות מן האבנים האלה בנים לאברהם

Elohìm yakhòl la’asòt min ha-abanìm ha-‘ele banìm le-Avrahàm

As can be noted, only in the Hebrew version does an assonance exist between the term “children” (banìm) and the term stones (abanìm). Not only that: this play on words that rhyme with each other fits perfectly into the technique of transmitting teachings based on assonances, alliterations, parables, oxymorons, and juxtapositions (the famous camel passing through the eye of a needle) used by the Tannaim to make their words stick in the disciples.

The example just mentioned can also be found in Aramaic (“stones”: ‘ebnaya ; “sons”: banaya), and yet there are many others that exist only by considering the Hebrew language as the original text underlying the Synoptic Gospels, as in the case of the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6, 12-13), where “forgive the trespasses” could correspond to the root nasa’, “trespasses” and “debtors” to nashah and “temptation” to nasah, or in the passage of the Benedictus (Luke 1, 68-79), a composition of three stanzas, with each seven lines, according to a typical Qumran scheme. In it, if translated into Hebrew from Greek, there are incredible assonances:

- “He has raised up for us a mighty savior born of the house of his servant David” or “save us from our enemies”, where “salvation” corresponds to the Hebrew term yeshu‘a, which is precisely the Hebrew name of Jesus (in Hebrew: “God saves”, or, simply “salvation”). The expression “to raise up a mighty savior…” could, therefore, be translated: “to raise a mighty Jesus”.

- “to show mercy (or grace) to our fathers”, where “grace” corresponds to the root ḥanan, which is then the same as the name John (Yoḥanan, in Hebrew: “God has shown grace”).

- “to remember his holy covenant”, where “to remember” corresponds to the root zakhar, that, to make it clear, of the Hebrew name Zakharyahu, that is Zechariah (in Hebrew; “God has remembered”), father of John the Baptist, who is then the one who declaims the passage in question.

- “the oath he swore to our father” (to swear an oath, or better, “to swear a swear” is a semitic play on words with the same root), where “to swear” is traced back to the root shaba‘, the same as Elishaba‘a, that is, Elizabeth (which in Hebrew means: “God has sworn”).

These are just a few examples of how a rigorous study, in exegetical and philological terms, can allow for a deeper understanding of the Gospel texts, enabling a more precise dating of them, a more accurate analysis of the historical, cultural, and religious context in which they were written, and a greater knowledge of the linguistic substrate that underlies them.

Criteria for the Historicity of Christ and the Gospels

Réné Latourelle (1918-2017), a renowned Canadian Catholic theologian, synthesized19, over a lifetime of studies dedicated to deepening the credibility of Christianity, a series of criteria that allow to attest the historicity of Christ and the Gospels:

- Criterion of multiple attestation. “One can consider a Gospel fact authentic if it is solidly attested in all (or most) of the sources of the Gospels”. This is the case, for example, of Jesus’ closeness to sinners, which appears in all the sources of the Gospels. This criterion is based on the convergence and independence of the sources.

- Criterion of discontinuity. “One can consider a Gospel fact authentic (especially when it comes to the words and attitudes of Jesus) that cannot be reduced either to the concepts of Judaism or to the concepts of the early church”. In this sense, one can mention Jesus’ use of the expression abba, “daddy”, to address God. The term “father”, understood in the sense of intimate and personal sonship towards God, not only by Jesus of Nazareth but by Christians in general, appears 170 times in the New Testament, of which 109 times solely in the Gospel of John, and yet only 15 times in the Old Testament, where it always has a meaning of collective, “national” paternity of God towards the Hebrew people.

- Criterion of conformity. “One can consider as authentic a saying or an act of Jesus that is not only in strict conformity with the era and the environment of Jesus (linguistic, geographic, social, political, religious environment), but also and above all intimately consistent with the essential teaching, the core of the message of Jesus, namely the coming and the establishment of the messianic kingdom”. Examples include the parables, the beatitudes, the prayers, and all teachings oriented towards the establishment of the “messianic kingdom”, in contrast, however, with the Jewish expectation of a political and earthly messiah.

- Criterion of necessary explanation. “If, faced with a significant set of facts or data, which demand a coherent and sufficient explanation, an explanation is offered that clarifies and harmoniously groups all these elements (which, otherwise, would remain enigmas), we can conclude to be in the presence of an authentic datum (fact, act, attitude, word ofJesus)”. How can this criterion be applied to the Gospels? For example, by admitting the presence of a “colossal” personality, that of Jesus of Nazareth, which is the only possible explanation in the face of the authority he attributes to himself, the strength in opposing the notables of the time and their prescriptions, the charisma exercised on the crowds and the disciples.

- A secondary or derived criterion: the style ofJesus, in practice his personality. R. Latourelle cites two different authors to explain this criterion, Reiner Schürmann and Lionel Trilling, stating that the style of Jesus of Nazareth is characterized by a rather singular self-awareness, solemn, majestic, yet, it went hand in hand with simplicity, kindness, gentleness, love for sinners, total consistency (in all the texts that write about him he never contradicts himself, and in this his case is the exact opposite of that of Muhammad, the founder of Islam) and a total lack of hypocrisy.

Archaeological Sources: Some Fundamental Findings

Since the end of the 19th century, and throughout the 20th, especially thanks to the impulse of the British Mandate in Palestine and the tireless work of Christian archaeologists (Franciscans, in primis) but also Israeli Jews, countless archaeological discoveries have been made in what was the environment of the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Indeed, it was archaeology that fostered the development of the Third Quest and, in general, the historical investigation around the figure of the Nazarene and the social, religious, and cultural context in which he moved, especially after the sensational discovery of the Qumran manuscripts (1947). It can be confidently stated, therefore, that archaeology has truly become a “fifth gospel”, or at least an indispensable source in the research around the “historical Jesus”

At the conclusion of this article, we report some of the most important archaeological findings that have characterized the last 150 years and that answer questions or objections from the most stubborn critics.

- Jesus of Nazareth would have never existed, as there is no evidence of the existence of Nazareth.

Let’s start with Nazareth, then. Until the 1960s, those who denied the existence of Jesus of Nazareth because no evidence of a city called Nazareth was found in the Hebrew Scriptures prior to the New Testament, had to reconsider. Indeed, we owe to Prof. Avi Jonah, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the discovery, in 1962, among the ruins of Caesarea Maritima, ancient capital of the Roman province of Judea, of a marble slab with a Hebrew inscription from the 3rd century BC that mentions the name of Nazareth.

In the following years, then, an excavation campaign conducted where the Franciscan Basilica of the Nativity now stands, was able to bring to light the ancient village of Nazareth and what is universally considered the house of Mary as a maiden (site of the Gospel stories of the Annunciation and the Incarnation) and, in very recent times, archaeological excavations conducted by Israeli teams have discovered, always in Nazareth, not only a house from the time of Jesus (1st century) near the “house of Mary”, but what could have been the very home of the family nucleus of Jesus, Joseph, and Mary.

- Around the Sea of Galilee, no traces of the villages mentioned in the Gospels have been found.

The Sea of Galilee, in northern Israel, has proven to be an open book, especially since the mid-1960s of the last century. The first to conduct excavations of significant importance were archaeologists like Virgilio Canio Sorbo (who, moreover, had already distinguished himself for his important works in the Judean desert, on Mount Nebo, at the Herodian fortress of Macherus, where Antipas beheaded the Baptist, at the royal fortress of Herodium near Bethlehem and especially inside the Holy Sepulchre), who, along with his collaborators, fully brought to light the village of Capernaum, discovering the house of Simon Peter and the famous Byzantine synagogue, which can be admired today and under which an older Roman building intended for the same use was discovered.

In 1996, however, a team led by the Israeli Jewish archaeologist Rami Arav found the remains of the Gospel village of Betsaida Iulia (the fishing village on the shores of the Sea of Tiberias from which, as written in the Gospels, various disciples of Jesus came).

- There is no evidence of the presence of a synagogue cult before the destruction of the Temple, in 70 AD.

The most recent discoveries have made it possible to demonstrate that, in the time of Jesus of Nazareth, in Palestine no inhabited center, even of minor importance, was without a synagogue. In addition to the splendid synagogue of Capernaum, in fact, starting from the 60s, numerous synagogue structures scattered throughout the Palestinian region and its surroundings have been discovered. It should be mentioned, in this regard, the very recent finding of two synagogues in Magdala (a village near Capernaum, always on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, dating back to the beginning of the 1st century AD).

Here, a fishing boat, intact, dating back to the 1st century AD and completely similar to those described in the Gospels, was also discovered.

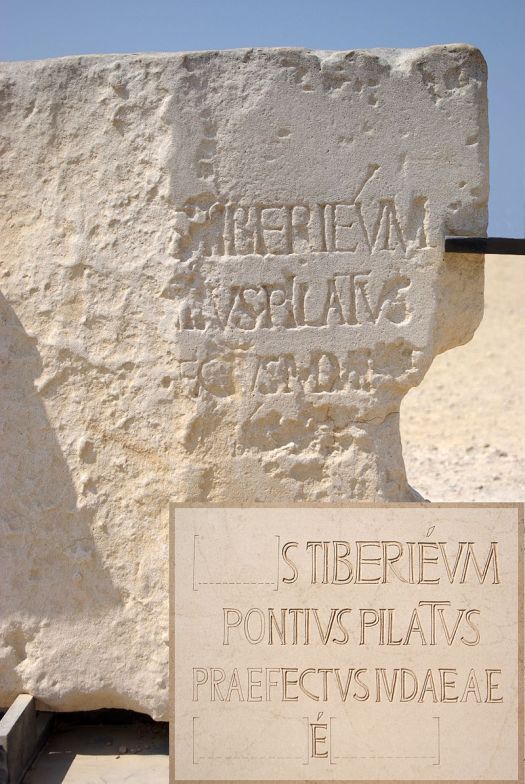

- The existence of Pontius Pilate has never been proven, as he was never mentioned in the official records of the Empire

In 1961, other archaeologists, this time Italians, led by Antonio Frova, discovered, in what is an inexhaustible source of data, namely the usual Caesarea Maritima, a limestone slab bearing an inscription referring to Pontius Pilatus Praefectus Judaeae. The stone block, since then known as the Pilate Inscription, appears to have originally been located on the exterior of a building that Pontius Pilate, described in the titulus as Prefect of Judea, had built for Emperor Tiberius.

Until the date of discovery, despite mentions by Josephus Flavius and Philo of Alexandria of Pontius Pilate, his very existence, or at least his actual position in Judea, whether as prefect or procurator, was doubted.

- The Gospel of John is a writing of a completely spiritual nature and has no historical value

In Jerusalem, two exceptional archaeological discoveries are the finding of the Pool of Bethesda (today the sanctuary of St. Anne) and the Gabbatha (Lithostrotos), of which all traces had been completely lost. Both were brought to light in the vicinity of the Temple Mount, exactly where indicated by the Gospel of John and perfectly corresponding to the description given by the latter.

In the first case, it is a pool with five porticoes surrounding a large basin about 100 meters long and ranging from 62 to 80 wide, enclosed by arches on all four sides, which lends plausibility to the episode of the paralytic (John 5:1-18) set at the “probatic pool”.

In the second case, however, that of the Lithostrotos, a paved courtyard of about 2,500 square meters was found, paved according to Roman use (lithostroton, precisely), and an elevated place, gabbathà (John 19:13), which could correspond to a tower.

The location of the place, right near the Antonia Fortress, at the northwest corner of the Temple Mount, and the type of remains brought to light, allow us to identify the seat where the governor, or praefectus, sat to issue sentences.

- We have no specific archaeological evidence of what the Temple was like in the time of Jesus.

In the area of the Temple Mount, razed to the ground by the troops of Titus in 70 AD, archaeologists have discovered the entrances to the esplanade with the double and triple gate to the south, bringing to light, just as they were destroyed by the Romans, the monumental remains to the west that include a paved road flanked by shops and the foundations of two arches, one called Robinson’s which supported a ramping staircase from the road, and another with a wider span, that of Wilson, which directly connected the temple mount to the upper city. Then, the arrangement of the portico called “of Solomon” is known, as well as other stepped streets that climbed up from the east, that is from the pool of Siloam. This allows us to imagine the gospel episodes about Jesus in the Temple, like the expulsion of the merchants (John 2:15).

- There are no historical confirmations regarding the technique of crucifixion and burial of those sentenced to death in Palestine at the time of Jesus.

It is true that elsewhere the condemned were not buried; instead, they were left to rot hanging on the crosses, at the mercy of scavengers. But in Palestine they sure were, especially to fulfill the precept of the Book of Deuteronomy 21, 22-23:

If anyone is found guilty of an offense deserving the death penalty and is executed, and you hang his body on a tree, you are not to leave his corpse on the tree overnight but are to bury him that day, for anyone hung on a tree is under God’s curse.

There is consensus among archaeologists about the location of Jesus’s crucifixion on the rock of Golgotha, now within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a site characterized by numerous excavations that have unearthed tombs there, dating back to before 70 A.D.

What we have just provided in this and the previous article are just a few insights, a drop in the maremágnum of studies surrounding the historicity of Jesus of Nazareth, but we hope they can serve as inspiration for those who wish to deepen their knowledge not only of a fundamental figure for all of humanity, but also of the customs, traditions, and distant times, which, indeed, have marked the history of the entire world.

Bibliography

Books

- Giuseppe Ricciotti, Life of Christ, Kissinger, 2006.

- Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, 2006.

- Vittorio Messori, Jesus hypotheses, St Paul Publications, 1977.

- Vittorio Messori, Patì sotto Ponzio Pilato?, SEI, 1992.

- Joachim Jeremias, Jerusalem in the time of Jesus, Fortress Press, 1969.

- David Flusser, Jesus, Varda Books, 2014.

- David Flusser, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity, Magnes Press, 1998.

- Jean Guitton, Le problème de Jésus, Aubier, 1992.

- Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, Image Books, 2007.

- Benedetto Croce, Perché non possiamo non dirci cristiani, Pannunzio, Torino, 2008.

- Jean Carmignac, Ascoltando il Padre Nostro. La preghiera del Signore come può averla pronunciata Gesù, Amazon Publishing, 2020.

- Jean Carmignac, Birth of the Synoptic Gospels, Franciscan Pr, 1987.

- Olivier Durand, Introduzione alle lingue semitiche, Paideia, 1994.

- Jean Daniélou, I manoscritti del Mar Morto e le origini del cristianesimo, Arkeios, 1990.

- James H. Charlesworth (ed.), Jesus and archeology, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006.

Articles

- Réné Latourelle, “Storicità dei Vangeli”, in R. Latourelle, R. Fisichella (ed.), Dizionario di teologia fondamentale, Cittadella, 1990, pagg. 1405-1431.

- Pierluigi Guiducci, “La storicità di Gesù nei documenti non cristiani”, in http://www.storiain.net/storia/la-storicita-di-gesu-nei-documenti-non-cristiani/ (consultato nel dicembre 2020).

- Pierbattista Pizzaballa, “L’archeologia ci parla del Gesù storico”, https://www.gliscritti.it/blog/entry/916 (consultato nel gennaio 2022).

Websites

- For further information on this issue, we refer to the article by Réné Latourelle, “Storicità dei Vangeli”, in R. Latourelle, R. Fisichella (ed.), Dizionario di teologia fondamentale, Cittadella, 1990, pp. 1405-1431. ↩︎

- Pier Luigi Guiducci, “La storicità di Gesù nei documenti non cristiani”, 2015, www.storiain.net/storia/la-storicita-di-gesu-nei-documenti-non-cristiani/ (in Italian) ↩︎

- Josephus Flavius (circa 37-100) was a Jewish writer and historian, who became an advisor to Emperor Vespasian and his son Titus Flavius Vespasian. In his Jewish Antiquities, he also mentions Jesus and the Christians. In a passage (XX, 200) he describes the stoning of the apostle James (who was the head of the Christian community in Jerusalem): “Ananus (…) assembled the sanhedrim of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus who was called Christ, whose name was James: and some others [or, some of his companions.] And when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned”, a description that matches that reported by the apostle Paul in the letter to the Galatians (1,19). In another passage (XCIII, 116-119) the historian indicates the figure of John the Baptist. ↩︎

- The term “Church Fathers” (or Fathers of the Church) refers, since the fifth century A.D., to the main Christian authors, whose teaching and doctrine are still considered fundamental for the Church’s doctrine, and whose writings form the so-called patristic literature. Among the most important, also considered saints and Doctors of the Church: Athanasius, Basil the Great, Gregory Nazianzen, John Chrysostom, Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine, Gregory the Great, John of Damascus. ↩︎

- Examples of Agrapha include the phrase, attributed to Jesus by Paul (in Acts 20, 35): “It is more blessed to give than to receive” (which is not found in any of the Gospels) or the one that Clement of Rome attributes to the Nazarene in his First Letter to the Corinthians (chap. 13): “As you do, so it will be done to you; as you give, so it will be given to you; as you judge, so you will be judged; as you are kind, so kindness will be shown to you”. The Logia, on the other hand, include sentences like those reported in ancient documents, especially papyri, such as those of Oxyrhynchus (a series of papyri dating from the first to the sixth century A.D., found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, containing fragments of ancient authors, like Homer, Euclid, Livy, etc., as well as Christian manuscripts, canonical and non-canonical), for example: “[Jesus says:] …and then you will see clearly to remove the speck that is in your brother’s eye” (cf. Matthew 7, 5; Luke, 6, 42). ↩︎

- Such term is a “semitism”. By semitism , it is meant the rendering into Greek – and, consequently, in subsequent translations, from Latin onwards – of a Semitic word or expression, or, more than the rendering, an actual calque. Through the study of the Gospels, indeed, and of the synoptic ones in particular (Mark, Matthew, Luke) it is possible to identify a Semitic substrate (Hebrew or Aramaic) then translated into a Greek that meticulously follows its syntactic, grammatical, and thought structure. Essentially, as reported by various biblical scholars, the synoptic Gospels (and more specifically those of Mark and Matthew) would be works in Hebrew or Aramaic but with Greek words. In the case of the term “brother”, the Greek αδελφός (adelphós ) translates the Hebrew and Aramaic אָח (aḥ ), with which, however, in the Semitic sense, are not meant only blood brothers, but also half-brothers, cousins, relatives in general as well as members of the same clan or tribe, or even of the same people. It is enough to consider that not even in modern Hebrew does a term exist to define a cousin: it is simply called “son of the uncle”. A similar phenomenon occurs, for example, with the term “son”, in Greek υιός (hyiós ), which translates the Hebrew בֵּן (ben) and the Aramaic בר (bar), where this word means not only the son of a father or a mother, but also a member of a tribe, a people, a nation, a religion (son of Abraham, of Benjamin, of Israel, etc.) or even a condition, a characteristic of the character and personality (as in the case of James son of Zebedee and his brother John, to whom – as we read in Mark 3, 17 – Jesus gave the nickname Boanerges (Βοανηργες), “sons of thunder”, to highlight their impetuosity. According to biblical scholars, this expression could derive from the Aramaic בני רגיש, bené ragàsh or ragìsh or even from the Hebrew – and also Aramaic – בני רַעַם , bené ra‛am . Both mean, precisely, “sons of thunder” or “sons of the storm”. In the Hebrew and Aramaic alphabet, indeed, the letters used for both terms, especially for some scripts like that typical of Qumran, are quite similar, which can lead to reading and transcription errors. ↩︎

- They are called in this way because many stories about Jesus are presented almost with the same words, which is evident if they are compared both in the original Greek version and in current languages, and which makes it possible to read many parts with a single “glance” (synopsis). ↩︎

- From the verb κατηχήω, kateheo, composed of the preposition κατά, katá, and the noun ηχώ, echo, meaning “echo”. The meaning of such verb is: “to resonate”, “to give echo”. ↩︎

- The root tanna (תנא ) is the Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew root shanah (שנה ), which is also the root in the word Mishnah (the Talmud, together with the Mishnah and the Tanakh, is a sacred text of Jewish Law. The Talmud and the Mishnah are exegetical texts that collect teachings of thousands of rabbis and scholars until the 4th century AD). The verb shanah (in Hebrew: שנה ) literally means “to repeat [what is taught]” and is used to mean “to learn”. The Tannaim operated especially under the occupation of the Roman Empire. ↩︎

- In the second Letter to the Corinthians, dated around 54 A.D., Paul speaks of the “reading of the Old Covenant”, or Testament, as well as a New Covenant not according to the letter, like the old one, but according to the spirit, that is, no longer inscribed on tablets, but on the heart ↩︎

- In this regard, the reflection of Francis de Sales, saint and Doctor of the Catholic Church, is interesting: “First of all, the entire Christian doctrine is in itself Tradition. Indeed, the author of the Christian doctrine is Our Lord Christ himself, who wrote nothing, except some characters while forgiving the sins of the adulterous woman. [—] Even more so, Christ did not command to write. For this reason, he did not call his doctrine “Eugraphy ”, but Gospel, and he commanded to transmit this doctrine especially through preaching, indeed he never said: write the Gospel to every creature; he said instead: preach. Therefore, faith comes not from reading, but from listening. In In Siate santi… nella gioia! – Testi scelti per cristiani immersi nel mondo, Itaca, 2018 (in Italian). ↩︎

- French Catholic priest and biblical scholar, he was a great exegete and translator of the Dead Sea Scrolls, of whose language he was one of the world’s leading experts. Thanks to the knowledge acquired on the subject, he realized that the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels impressively mirrored the type of Hebrew used in the Qumran scrolls (until 1947 it was believed that the Hebrew language in Palestine had died out by the time of Jesus, while the discovery of hundreds of manuscripts in the caves around the Dead Sea confirmed that Hebrew, instead, was still in use, albeit as a “learned” language, at least until the end of the Third Jewish War, in 135 AD). Based on an in-depth linguistic study of such Gospels, lasting two decades, he became an advocate of their original composition in Hebrew, rather than in the Greek in which they have come down to us and therefore of their dating around the year 50. Carmignac presented this thesis in the work La naissance des Évangile synoptiques , published in English under the title Birth of the Synoptic Gospels. ↩︎

- In Exegesis of the Dominical Logia, of which Eusebius of Caesarea cites some excerpts in The Church History (Book III, chap. 39), Papias writes: “Mark, having become the interpreter [hermeneutes] of Peter, wrote down accurately everything that he remembered, without however recording in order what was either said or done by Christ. For neither did he hear the Lord, nor did he follow Him; but afterwards, as I said, (attended) Peter, who adapted his instructions to the needs (of his hearers) but had no design of giving a connected account of the Lord’s oracles. So then Mark made no mistake, while he thus wrote down some things as he remembered them; for he made it his one care not to omit anything that he heard, or to set down any false statement therein”. Similar information is provided by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Irenaeus, and Eusebius of Caesarea himself. ↩︎

- Information confirmed by Papias (op. cit.): “Matthew put the logia in an ordered arrangement [sunetaxato] in the Hebrew language [hebraidi dialectō], but each person interpreted them as best he could”. Irenaeus (a disciple of Polycarp of Smyrna, who in turn was a disciple of the evangelist John), writes in 180 AD, in his work Against Heresies : Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia”. Similar very ancient testimonies come through Pantaenus, Origen, Eusebius of Caesarea. ↩︎

- The oldest fragment of the canonical New Testament corresponds precisely to one of the Gospels, that of John, and is Papyrus 52, also known as Rylands 457, found in Egypt in 1920 and dated between the 2nd and 3rd century A.D.. From a historical point of view, the closeness between the publication of the work itself (as we have written, between 60 and 100 AD) and the oldest written testimony of it found is impressive, if we consider that the first written copy of the Iliad is from 800 A.D. while it is believed that the work itself was probably written around 800 B.C. ↩︎

- One of the first Church Fathers to note the presence of “discrepancies” between one Gospel and another was Augustine, who, however, spoke of a concordantia discors. ↩︎

- He discussed this in his book A l’écoute du Notre Père ↩︎

- In this regard, see . works by scholars such as Flusser, Meier, and others. ↩︎

- Réné Latourelle, “Storicità dei Vangeli”, in R. Latourelle, R. Fisichella (ed.), Dizionario di teologia fondamentale, Cittadella, 1990, pagg. 1405-1431 (in Italian). ↩︎